In the summer of the 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy sent Averill Harriman to Africa to meet with Patrice Lumumba. After doing so, Harriman advised JFK that he did not think Lumumba was a communist. But since there was little the USA could do unilaterally, he should support Dag Hammarskjold at the UN but not openly ally himself with Lumumba. It was too risky. (Muehlenbeck, p.75; Newman, p. 293). At that time, Kennedy took that advice.

But as historian John Morton Blum has noted, the CIA seems to have been aware of Kennedy’s sympathy for Lumumba. The CIA station chief, Larry Devlin, considered Kennedy’s backing of Hammarskjold a rather radical proposal. This seems to have been part of the reason that the Agency considered eliminating the elected leader and installing an unelected one. (John Morton Blum, Years of Discord, pp. 23-24). There is some evidence in State Department files that seems to endorse this interpretation of events. (Mahoney, p. 71)

Towards the end of the Eisenhower/Nixon administration, the White House had decided to retreat from Hammarskjold. The State Department issued a fairy tale like press release stating that it had “every confidence in the good faith of Belgium.” (Mahoney, p. 55) But it was likely even worse than that. For as journalist Jonathan Kwitny added:

In New York, the US warned Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold…that if the UN tried any compromise that would restore Lumumba to power, the US would make “drastic revision” of its Congo policy, implying unilateral military action. The US would not tolerate the return of Lumumba, the only man ever to hold office by legitimate vote of the Congolese people. (Kwitny, p. 67)

Lumumba was killed three days before Kennedy took office. Unaware of this fact, JFK ordered new plans for Congo. His policy made it clear that he would be backing Hammarskjold’s attempt at military neutralization, the freeing of all political prisoners (clearly aimed at Lumumba), and the blocking of the Katanga secession. To hammer home this split in policy, Kennedy invited Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana--an ally of Lumumba--to Washington. (DiEugenio, Probe Magazine, Vol. 6 No. 2)

Hammarskjold predicted there would be a backlash to Kennedy’s policy and there was. Ambassador Clare Timberlake got in contact with CIA Director Allen Dulles and Joint Chiefs chairman Lyman Lemnitzer and told them about Kennedy’s new plans. Timberlake then teamed with CIA station chief Larry Devlin to attempt to blunt Kennedy’s new policy and back the Kasavubu/Mobutu usurpers. When Kennedy got news of this he recalled Timberlake.

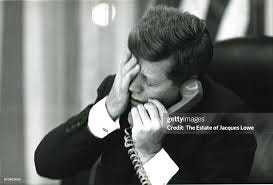

In February of 1961 Kennedy was playing with his children in the Oval Office, with photographer Jacques Lowe taking pictures. He got a phone call from his United Nations ambassador Adlai Stevenson. Stevenson informed him, almost one month after he was slain, that Lumumba was dead. This was his reaction.

Perhaps no photograph taken during his presidency defines the differences between Kennedy and those who came before him and those who came after. It is difficult to imagine, say Lyndon Johnson or Richard Nixon, reacting like this to the death of a revolutionary leader in Africa.

Why did Allen Dulles and the CIA not tell Kennedy about Lumumba’s demise? Perhaps because they thought maybe he would suspect that the Agency had a role in it? Senator George Smathers once said something about a discussion he and Kennedy had:

“…the CIA frequently did things he didn’t know about, and he was unhappy about it. He complained that the CIA was almost autonomous…and he wanted to get control of what the CIA was doing.” (The Assassinations, edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, p. 329)

The killing of Lumumba caused Hammarskjold to sponsor a UN resolution authorizing the use of force to stop the Katanga secession and clear out mercenaries in the breakaway state. Irish diplomat Conor Cruise O’Brien was placed in charge of about 19,000 troops from non-colonial nations. O’Brien ordered two operations to implement the resolution, Rumpunch and Morthor. The first is deemed as successful, the second as less so. And there is a question about whether Hammarskjold approved Morthor.

But Morthor did provoke the British to call a meeting between Hammarskjold and Katanaga’s leader Moise Tshombe for an armistice. As we all know ,the Secretary General’s plane—the Albertina-- did not make it to Ndola, Rhodesia on the night of September 17, 1961. At the time, the Rhodesian authorities deemed this as an accident, a crash. Today, after work by both essayist Lisa Pease and author Susan Williams, very few informed people believe it was anything but an act of sabotage. In fact, as was recently discovered, the new ambassador to Congo--Edmund Gullion—sent a cable to Washington suspecting that the plane has been shot down by a Belgian mercenary pilot. (Article by Julian Borger, The Guardian, 4/4/2014). Today, as expressed in the 2019 film Cold Case Hammarskjold, many believe the plane was sabotaged by the terrorist group SAIMR as part of a codenamed secret assassination operation called Celeste.

Why is there so much suspicion about Hammarskjold’s demise? Let us look at some of the evidence. Seven witnesses testified that they saw another plane in the sky at the time the Albertina was descending. That plane moved away once the Albertina was downed. (Lisa Pease, “Midnight in the Congo”, Probe Magazine, Vol. 6 No. 3) Two police officers also saw a flash of light in the sky. Another witness, who refused to speak to the Rhodesian Commission, also said he saw another plane above and behind the Albertina. Further, he saw two Land Rover type vehicles immediately set out at high speed to the site of the crash. (Ibid)

No alarm was sounded at the Ndola Airport when the Albertina did not make its scheduled landing. In fact, the man in charge, Lord Alport, sent his employees home. Two American Dakota planes were on the airstrip with engines running, which means their communications were working. Oddly, no search and rescue operation was started until about ten hours afterwards. One of the most curious aspects of the crime scene is that although everyone else on the plane was badly burned, Hammarskjold’s body was not. (ibid) But, as Susan Williams proved in her book on the subject, perhaps the most bizarre aspect of the crime scene is this: when his body was discovered, there was an ace of spades playing card inserted into Hammarskjold’s collar.

JFK admired the Secretary General and met with him on the Katanga issue in New York City. (JFK vs. Allen Dulles, by Greg Poulgrain, p. 151) Reportedly, he had called in a Swedish diplomat when he learned of Dag’s death. He told him that Hammarskjold was the greatest statesman of the 20th century. He could never hope to achieve the stature he had. Whatever the cause of the Secretary General’s death, whether it be a shootdown or sabotage by planting a bomb on board, Hammarskjold’s death seemed to galvanize Kennedy. From this point on, he took over the Congo mission, determined to carry out what Hammarskjold had begun.

A week after Hammarskjold’s murder, JFK went to the UN. He talked about:

…the exploitation and subjugation of the weak by the powerful, of the many by the few, of the governed who have given no consent to be governed, whatever their continent, their class, or their color. (Poulgrain, p. 152)

Kennedy also added that “Let us here resolve that Dag Hammarskjold did not live or die in vain.” (DiEugenio, Probe Magazine, Vol.6 No. 2) He now decided to appoint Edmund Gullion as permanent ambassador to Congo. No ambassador in the JFK administration was more secure in his access to the Oval Office than Gullion. (Mahoney p. 108). This shows how important Kennedy thought Congo was. In fact, it became a kind of testing ground for his ideas concerning American power in the Third World.

To supplement Gullion in the White House, Kennedy appointed the self-styled maverick George Ball as special adviser on Congo, the man who would soon oppose Lyndon Johnson on Vietnam. All three men now decided to find a leader to replace Lumumba and to forge a political center in Congo. That man turned out to be Cyrille Adoula, a moderate labor leader who was a decent man, but had little of the dynamism and charisma of Lumumba. With a new team in place, Kennedy now allowed UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson to vote for a resolution allowing use of force to deport mercenaries and advisory personnel out of Katanga. (Op. Cit. DiEugenio)

Tshombe decried this resolution—after all the mercenaries were Belgian, British and French-- and declared he would fight its implementation. And, in fact, there were now serious skirmishes between his tanks and UN troops over access to the airport. These hostilities ended up in acts of terrorism by Tshombe. He used churches and hospitals to fire upon the UN troops. When the new Secretary General, U Thant, began to waver in the face of criticism over casualties, Kennedy gave him permission to expand the war without consulting with any other allies.

Kennedy also decided to use economic warfare against Katanga. A Belgian/British mining company named Union Miniere had been supplying Tshombe with money to finance his army e.g. hiring mercenaries. Kennedy asked them to curtail their payments. When they refused, he threatened to unleash a huge attack on Katanga, and then give the Union Miniere assets over to Adoula in a new unified Congo. That threat worked and the payments were significantly reduced. When Tshombe requested a visa to appear before congress to plead his case, Kennedy denied the request. Third, Kennedy now got George Ball to agree on military force if needed. (Op. Cit. DiEugenio)

Kennedy had set his own table.

On December 24, 1962 Katangese forces shot at a UN helicopter and an outpost. The UN now decided to attack with a combined land and air strike which was code named Operation Grand Slam. In less than a week, Elizabethville, the capital of Katanga, was under siege. By January 22nd Katanga’s secession was finished. JFK wrote a note to a special assistant on Congo: they were now entitled to “a little sense of pride.” (Mahoney, p. 156)

Exhausted, the UN was now ready to pull out. But in an extraordinary effort, on September 20, 1963, Kennedy went to New York again, to plead with them not to do so. His message was to complete what they have started and protect this new nation. It worked. The UN voted to keep the peacekeeping mission intact for another year.

But in October and November, things began to spin awry. Kasavubu decided to dismiss parliament. This ignited a simmering leftist rebellion by Lumumba’s second, Antoine Gizenga. Kennedy wanted a retraining of the Congo’s army by area specialist Colonel Michael Greene. U Thant and Kennedy agreed with Greene that there should be African representation in the leadership of the program. (Mahoney, pp. 226-27)

But the Pentagon, as in many matters, did not agree with Kennedy’s ideas and plans. Mobutu, who had betrayed Lumumba, had now become a favorite of the Fort Benning clique in the army. That group would eventually sanction the infamous School of the Americas, which would spawn a whole generation of rightwing Third World dictators. In November, weeks before his death, he asked for a progress report on the Greene plan. Stymied by Army Chief Earle Wheeler, the Pentagon had done little, and it blamed the lack of progress on the UN. What they wanted now was a complete American oriented effort run by that Fort Benning crowd. (ibid)

With the death of Kennedy, that is what they were about to get. With disastrous results for Congo.

BTW, Shelly, John Wayne shot part of his pro Vietnam War movie The Green Berets at Fort Benning. They treated him royally and he paid for next to nothing.

The Fort Benning crowd was the staff run by Wheeler who manned the School of the Americas, located in I think Panama Canal Zone at the time, but run out of Benning and later transferred there directly. It was infamous for training men wno became dictators in the Third World. Mahoney says they liked Mobutu.